East and West view the Russians differently. Why? An answer from life experience

"Stop Putin," one of the 420 residents of the idyllic Swabian village of Ochsenwang wrote on a window in large blue letters. Since Putin's invasion of Ukraine , Russophobia and its big brother, Russophobia, have become commonplace in politics and media, as if "the Russians" were at Germany's doorstep. It's no wonder that blanket judgments are taking root precisely in places where hardly anyone has any experience with Russians, such as the Swabian Alb.

Anyone who attempts to differentiate is immediately labeled a "Putin sympathizer," along with the accusation that they are succumbing to Russian propaganda and spreading its narrative. It's obvious: attitudes toward Russia are dividing Germany. Especially in the East, a majority does not subscribe to the simplistic image of the Russian as the enemy.

Rarely have so many readers written to the Berliner Zeitung in emails and letters as after Baerbock's Foreign Ministry issued a "guideline" to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the liberation without the liberators. In 2022, the Green Party politician celebrated EU sanctions with the words: "This will ruin Russia."

In fact, such statements undermine the goal of Western democracies. Instead of opposing the Putin government's aggression, the majority of the Russian population stands firmly behind their war-mongering leader . Why should they feel sympathy for the Russophobes in the West and seek regime change, a less authoritarian, less nationalistic alternative to Vladimir Putin ?

Practiced in the East in relations with the Soviet UnionIn eastern Germany, Russophobic rhetoric provokes more opposition than in the west, although the desire for differentiation is not due to Putin's certainly very active sabotage and dissemination of lies. Rather, the fundamental sympathy for the Russian people stems from decades of experience.

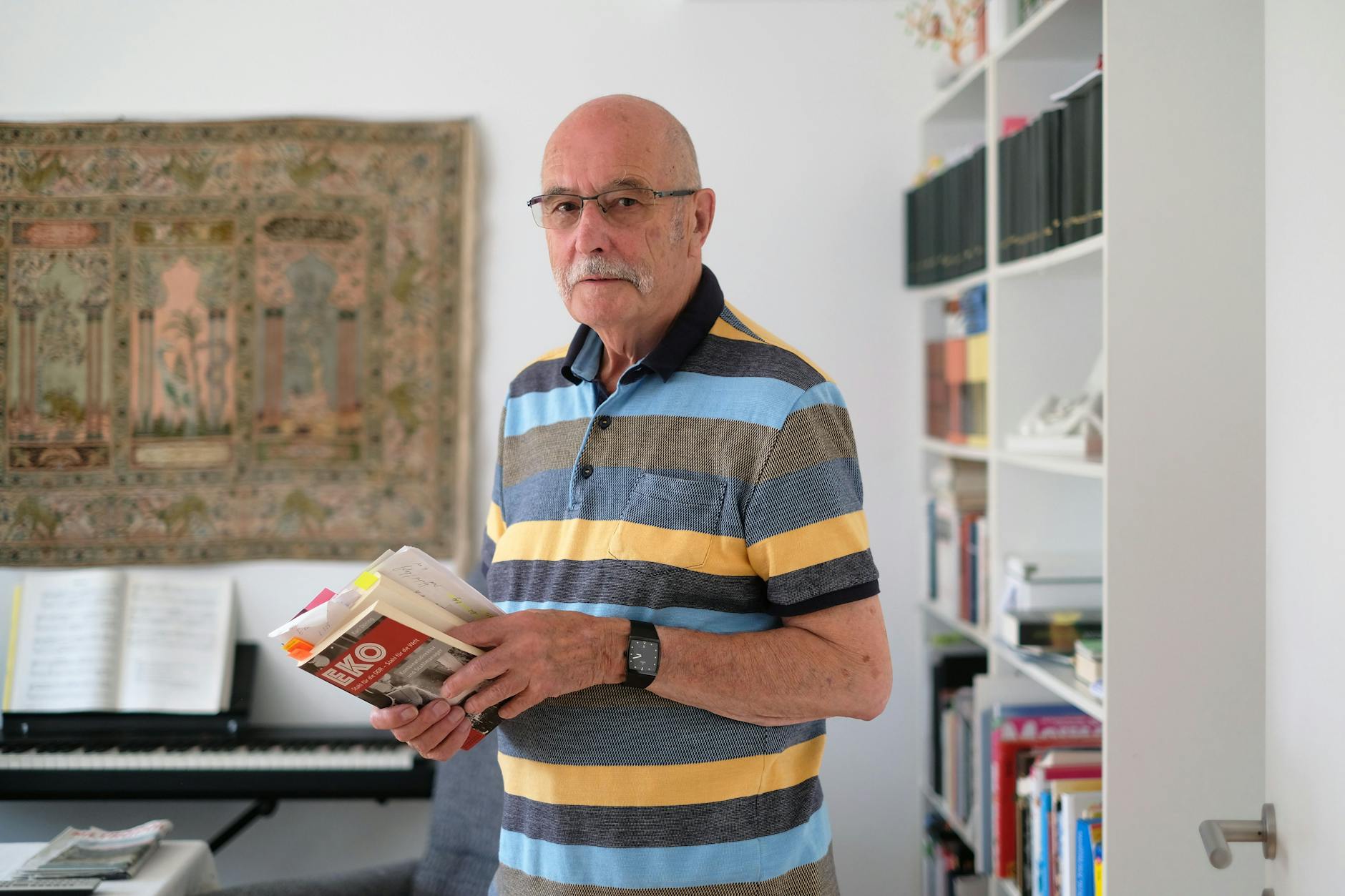

“We were experienced in German-Soviet relations,” says Eckardt Netzmann, for example, who for many years was the general director of the Ernst Thälmann Heavy Machinery Combine (SKET) based in Magdeburg. “We were right in the middle of it.”

The topic concerns many who lived in the GDR, given the alienation not only from Russia but also from China: "Who do we want to cooperate with in the coming decades? What should our geopolitical integration look like?" Netzmann asks. Born in 1938, Netzmann is concerned about his children and grandchildren and is not alone in this at the quarterly General Directors' Salon at the home of publisher Katrin Rohnstock in Pankow.

One person who had a particularly intense experience of the former Soviet Union is Karl Döring, 88. The German manager studied and earned his doctorate in Moscow and became known as the general director of the Eastern Ironworks Combine in Eisenhüttenstadt. The EKO always sourced iron ore from the Soviet Union, later from Russia, and exported it there.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Karl Döring played a key role in the successful transition of EKO Stahl AG to a market economy, serving as CEO until 1994 and then as Technical Director until 2000. He served on the board of directors of the Treuhandanstalt (Treuhand Agency) until the end of 1990, when he was expelled as an East German. During that time, he had many very diverse experiences with West Germans, some of them disturbing.

His first, short answer to the question of why East and West view Russians and the former Soviet Union so differently is: “Actually, it’s quite simple – it’s due to our biographies, or rather those of the inhabitants of the former Federal Republic of Germany.”

For people from Döring's generation of East German war and post-war children, the relationship with Soviet people began early and intensely. The eight-year-old spent the last weeks of the war in assigned accommodation on a former municipal estate in Großenhain (Saxony).

Touched by prisoners of warThe Soviet prisoners of war employed there in armaments production, the "Russians," sought contact, and the guards, Wehrmacht personnel unfit for military service, did not shoo the farm children away from the barbed wire fence: "Many small toys, made in the factory in unobserved moments, ended up in our hands," Karl Döring recalls. Because the apartment was adjacent to the outbuildings, he heard the melancholy singing of the prisoners of war in the evenings—his first contact with Russian culture.

Even after Großenhain was liberated without a fight on May 22, 1945, and the Soviets set up a supply unit on the estate, friendly relations with the Red Army soldiers developed. The children received flour, "and I was allowed to ride a horse for the first time," Karl Döring recalls: "A connection developed on a very personal level."

In March 1953, after Stalin's death, he stood guard of honor in front of the Stalin portrait at his school with an air rifle. Even later, the "unbreakable friendship, the brotherhood, the cooperation" remained omnipresent – according to official propaganda, relations with the Soviet Union were always supposed to be viewed as 100 percent positive. Of course, that didn't correspond to reality, but it didn't give him any cause for concern at the time: "I accepted it as a given and lived it myself." But beyond the state doctrine, many GDR citizens had personal acquaintances, impressions, experiences, and encounters with people from the Soviet Union: "That's what distinguishes the East."

Fear of communists behind the Iron CurtainIn the West, the situation was reversed, but just as clear: The explanation that the Iron Curtain ensured that "the communists wouldn't overrun us good people" was, according to Döring's observation, "carried on in all instances, considerations, and conversations in the Federal Republic of Germany." Hardly anyone had personal contact with people from the Soviet Union, and people only imagined "the Russians" anyway, instead of perceiving the diversity of Soviet people: "Traveling to the country—that wasn't even planned."

Karl Döring illustrates this statement with a personal story: In the summer of 1998, the Chief Technical Officer of Cockerill-Sambre – the Belgian company had acquired EKO in 1995 – retired. Jean Lecomte, who had been responsible for EKO on the Cockerill board, now had time. He had never been to Russia before and now wanted to go, together with his wife. He expressed the wish: "Couldn't you and your wife accompany us?"

The widely traveled steel executive had heard only negative things about Russia his entire life – from school to current news reports, as he explained to Döring. Due to insecurity, the man didn't dare travel alone. Therefore, the two couples – Döring's wife is Russian – decided to take a joint tour: "At the end, we said goodbye to a reformed and deeply impressed Lecomte couple at the airport in St. Petersburg. Prejudices against Russia had been dispelled."

That same year, Karl Döring visited the Lebedinsk ore processing plant in the Kursk Bulge, where one of the fiercest battles of World War II had raged in 1943, killing several hundred thousand soldiers. There, the general director of the Soviet ore combine had a Cathedral of Reconciliation built, which also commemorates the fallen Wehrmacht soldiers. Döring calls it an example of "how the people in the USSR and later in Russia reacted to the German actions in the World War."

Contrary to popular belief, these contacts did not remain at the official, formal level—partly because the socialist economy thrived largely on improvisation, on informal give and take. Red Army soldiers helped with the harvest and, to everyone's delight, were given a decent feast with a barbecue and vodka, including a sausage package.

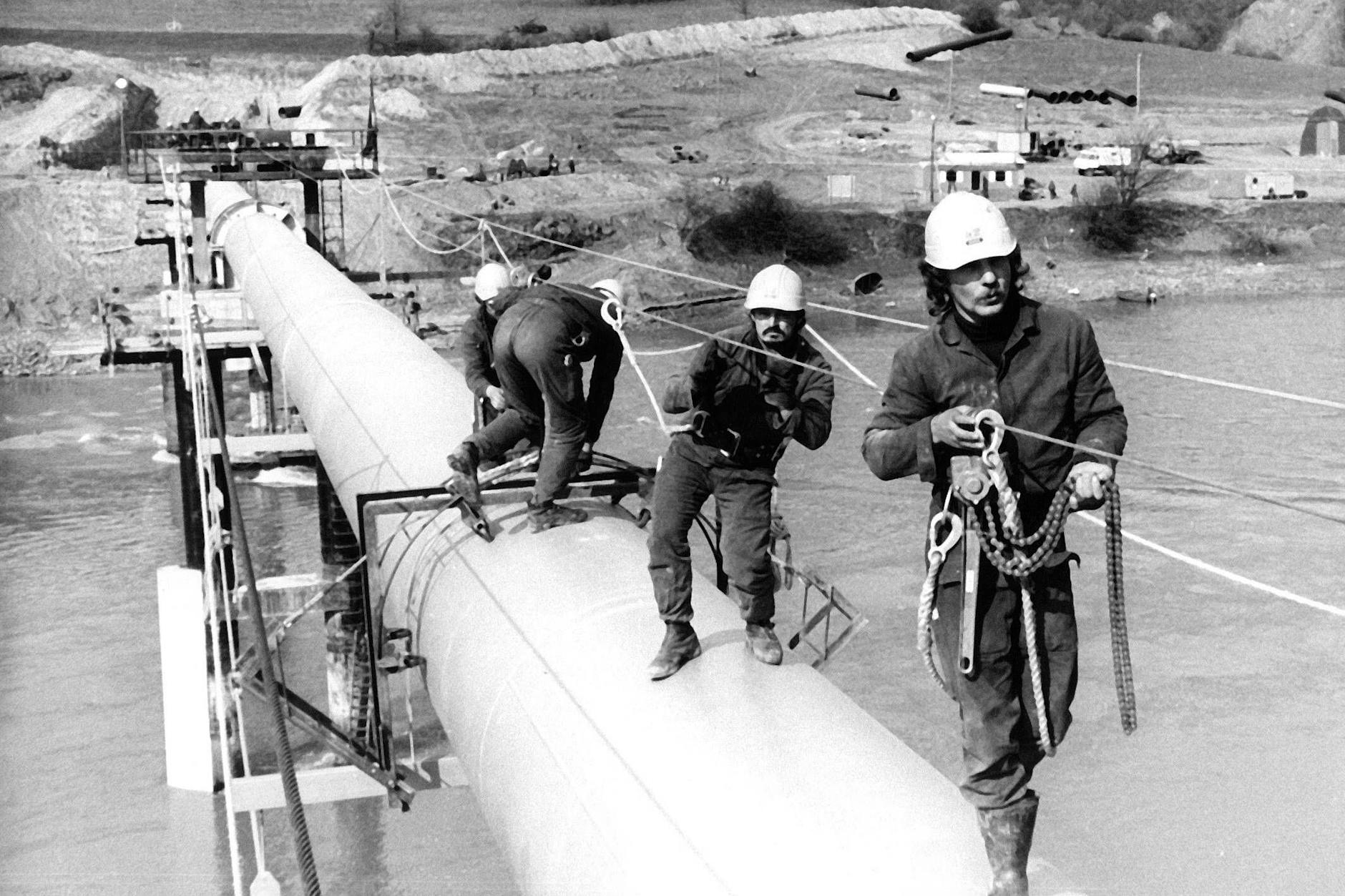

The tens of thousands of young people who worked on the construction of natural gas pipelines in the Soviet Union brought formative experiences home to their families, meaning that many more people had close, direct contact with the Soviet Union. The construction of the Druzhba natural gas pipeline through Ukraine alone led to 150 binational marriages.

Karl Döring also reports such examples: The steel industry received help from Soviet soldiers during difficult times, especially in winter, even in direct production. On Soviet holidays, people visited the Soviet barracks. In the Ministry of Mining, Metallurgy, and Potash, he reports, the tradition of friendship trains was maintained: "Once a year, 200 activists and their spouses traveled free of charge on a special train to the USSR, to regions where the steel industry was located."

The grandchildren “think less firmly”Döring, Deputy Minister of Mining, Metallurgy, and Potash from 1979 to 1985, led the special train to Ukraine. Soviet metallurgists traveled in return: "Each time, we worked joint production shifts at two plants. Those were encounters!" Because the spouses always accompanied the trips, and the project ran for eight years, the number of participants was quite large. And finally, there's the story of EKO's survival after the fall of communism: "This was achieved almost exclusively thanks to partner deals with the Soviet Union."

Döring's conclusion: "My experiences are positive, of course." His children think the same, but: "The grandchildren think much more unstable." And he recalls the insincerity of West German politics, which he experienced firsthand as a member of the Treuhand supervisory board until his dismissal during a crucial period: The Treaty on Partnership, Friendship, and Cooperation between Germany and the USSR, unanimously adopted in the Bundestag on April 5, 1991, had a predecessor – signed on November 9, 1990, by Helmut Kohl and Mikhail Gorbachev: "We have comprehensive contractual obligations from the period of upheaval." Yeltsin confirmed that Russia was entering into these treaties as the legal successor to the USSR: "The fact that we hear nothing more about this today is typical of the situation."

Like Egon Bahr , one of the most important architects of German Eastern policy under Willy Brandt (both SPD), Karl Döring was one of the participants in the Petersburg Dialogue. The East German quotes one of Bahr's key statements: "The transatlantic alliance is indispensable for Germany. But Russia is immovable. Russia will always be our great neighbor in the East." A fact, just like the widely repressed fact that a third of Europe lies in Russia.

It's the same neighbor that former Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock (Greens) wants to see "ruined." Karl Döring currently sees no sign of rapprochement: "Current policies are fueling hostility."

Berliner-zeitung