There's Only One Real Way for Democrats to Disarm Texas Gerrymandering

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

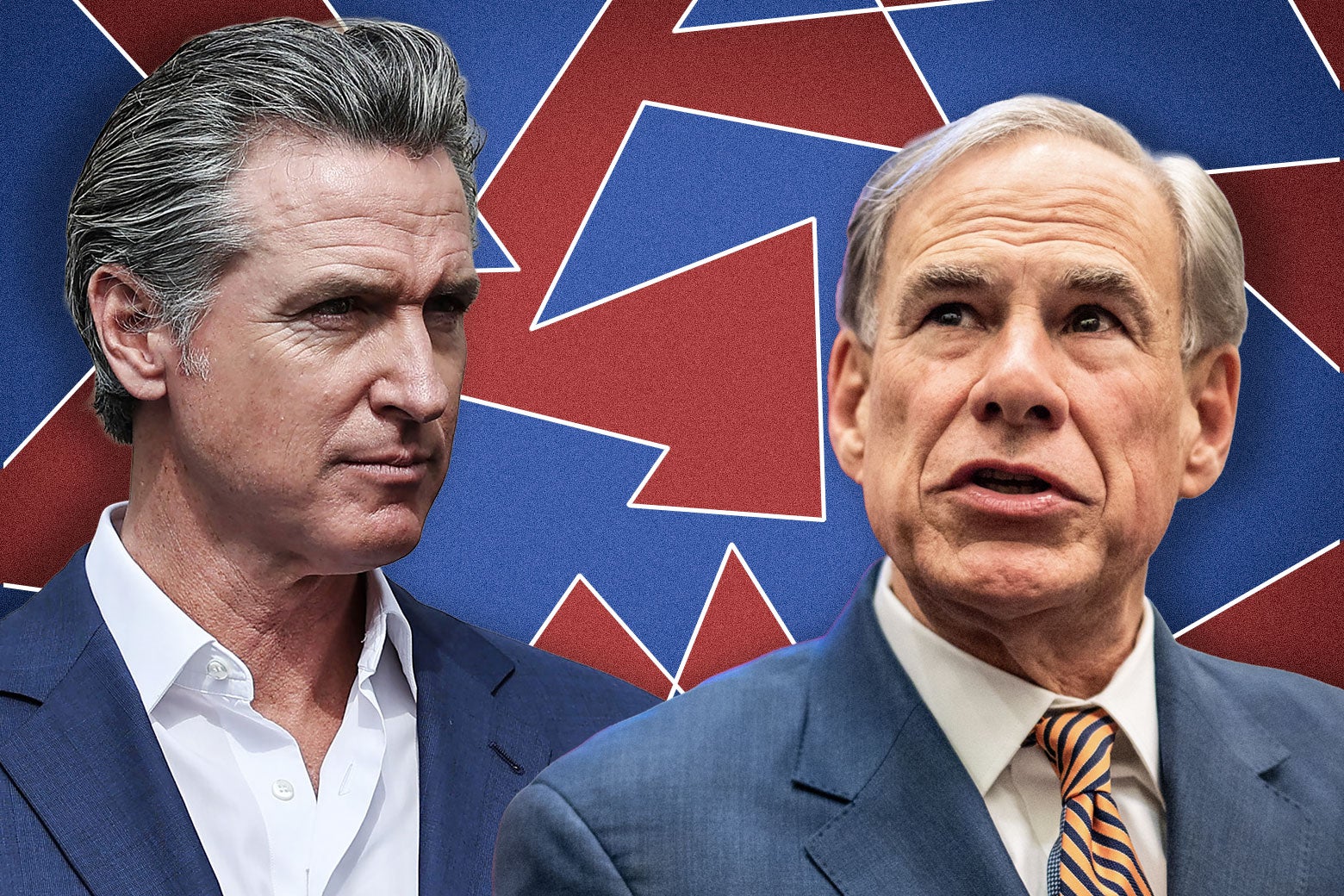

The summer battle over partisan gerrymandered new maps has reached a feverish pitch this week, with Texas Democrats ending their blockade of a session to redraw the state's maps in favor of Republicans, Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom promising to amend the state's constitution to respond in kind , and Republican Speaker of the House Mike Johnson pledging to fight California's efforts to combat Texas' electoral machinations.

If this all sounds like a spiral that is slowly escalating out of control with no end in sight, well, that's because it is. As experts in election law and constitutional law , we think we have an idea to potentially quell the conflict before it goes any further.

First, it's important to think of the gerrymandering wars as you might an actual war. So imagine you are the head of a free nation. You learn that a hostile foreign state intends to launch a devastating nuclear attack against you. How might you stop it?

Students of history will recall the lessons of the Cold War, when the United States and Soviet Union used the mutual threat of retaliatory strikes to prevent all-out nuclear destruction. President Donald Trump started this latest partisan conflict by calling on Texas legislators to gerrymander the state's maps, and now we are on the verge of a similar standoff for American democracy.

In this tit for tat, though, California's threats to respond have thus far proven ineffective. Despite Newsom's very public threat to retaliate with a state redistricting plan that would neutralize any Republican gains, Texas legislators are plowing ahead with their own gerrymandering efforts. That is the opposite of what happened after retaliatory threats during the Cold War. What gives?

For one thing, Texas officials may believe they are calling California's bluff. To gerrymander its own maps, after all, would require California to jump through quite a few hoops , including an expensive state-level initiative to change the constitution in a special election this November.

But, more fundamentally, Republicans like Texas Gov. Greg Abbott are gleeful that California is talking openly about playing by the same, democracy-distorting rules because it allows them to argue that Republicans are gerrymandering only because California Democrats are. At the end of that line of argument is a vicious cycle in which more and more states retaliate with gerrymandered maps of their own, eliminating even the few competitive House districts that remain .

There is a way out of this death spiral. It involves a simple concept: automation. By enacting a law that would automatically gerrymander California's maps if and only if Republican-controlled legislatures do so first , California officials can make clear that the choice is entirely in the hands of Republican state legislators. In other words, just as automated nuclear retaliation systems helped prevent a horrific strike during the Cold War, a similar approach can stop the gerrymandering race to the bottom before it's too late.

Here's how the plan would work. A blue state like California, or perhaps New York, could adopt a system similar to the one it presently has , with an independent bipartisan commission drawing the state's congressional map. Like the current system, the law could require the commission to account for certain criteria like making districts contiguous and compact. Then the new system would add a critical, novel factor: The commission must draw congressional districts to ensure national partisan balance so the percentage of Republican and Democratic seats in Congress closely corresponds to the number of votes for Republicans and Democrats nationwide.

This means that California's maps would automatically respond to red states' partisan gerrymanders. For example, if Texas implemented its new and more aggressive partisan gerrymander, California's new and automatic redistricting system would respond in kind. The result would be that, as much as practically possible, California's system would neutralize Texas' partisan gerrymander.

So far, this might sound like exactly what Newsom has proposed. But there is a critical difference. The problem with the governor's approach is that because it is an ad hoc political response to Texas' gerrymander, it virtually guarantees a continued race to the bottom. Texas will be heavily gerrymandered, and so will California. And so will the next red state and the next blue state , and potentially on and on. That's not the best outcome we can hope for. Representation of Democrats in Texas and Republicans in California matters too. We should aim for a national map without partisan gerrymandering in either red states or blue states.

This is where a principled, automated redistricting system in California would make all the difference. Newsom's approach is aimed at teaching Texas that if it gerrymanders, then California likely will too. What Texas doesn't know, however, is that if it doesn't gerrymander, then neither will California—a legitimate concern given the latter's race to put its new partisan maps on the 2025 ballot.

Under an automated redistricting system, by contrast, California's independent, bipartisan commission would be authorized to redraw the state's maps only if Texas acts first. And, just as significantly, if Texas were to eventually undo its own gerrymander, an automated redistricting law would ensure that California's independent commission would do the same.

In short, by tying itself to the mast of an independent redistricting process with national partisan balance as a strict goal, California can guarantee that no state—neither it nor Texas—gets caught unilaterally disarming in the partisan gerrymandering wars. Just as importantly, it wouldn't require Texas to formally agree to a trick. And although this should not be the only consideration, adding national partisan balance as a required factor to an independent redistricting process strikes us as more salable to the California voting public than an overt call to embrace gerrymandered maps.

There are important technical details to work out to make this principled, automated system work. How will it measure national partisan balance? When will it issue its maps after the decennial census? Must it wait for every other state to issue its maps, or just traditionally red states like Texas? One question that shouldn't arise, however, is whether this response would violate the US Constitution. The Supreme Court has already said it won't undo even the most extreme partisan gerrymanders . We wish the justices had decided differently, but in the world the court has created, a principled and automatic counter-gerrymander must surely survive.

Ultimately, of course, even if California adopts a principled, automated redistricting system, Texas may gerrymander anyway. But at the very least, this approach promises what tit-for-tat political retaliation cannot: hope to end the partisan gerrymandering wars.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.