Old Iron. The Decline of Intel, From Giant to Small Fish

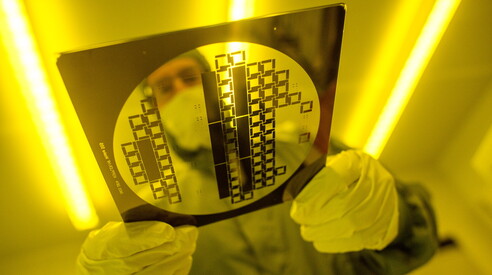

Getty Images

Magazine

From the foundations of Silicon Valley to the struggle for survival. The crisis of Californian society is a parable on the pace of technological innovation.

On the same topic:

There are companies that make profits and companies that make history. Then there are those that can do both, like Intel. A brand that is much more than just a company with its products, managers, and markets . Without Intel, there would be no Silicon Valley as we know it today. The world would not have experienced a personal computer boom like the one in the 1980s, and giants like IBM and Microsoft would not have become so colossal. The Internet would not have developed with the speed and scale that characterized its takeoff . The entire digital ecosystem we take for granted today was shaped by the microprocessor revolution introduced by Intel, and anyone old enough to remember the 1990s cannot help but connect the “Pentium” brand and the iconic “Intel Inside” marketing campaign to the idea of speed, computing efficiency, and computing power.

The problem is that today Intel seems to be struggling both to make a profit and to change its history, and risks being relegated to the memory of times gone by. The nightmare on the horizon is to join the list of those brands analyzed in university master's degrees, when they try to explain what happens to those who don't immediately grasp innovation: Kodak, Blockbuster, Nokia, BlackBerry, Motorola, Polaroid, Toys 'R' Us, Myspace.

The nightmare of ending up in university master's classes next to Kodak, Blockbuster, Nokia, BlackBerry, Motorola

It's not a given that it will end this way; Intel's fate is still being written and could even be that of a great rebirth. However, the Santa Clara, California-based company is undoubtedly experiencing the most difficult phase of its nearly sixty years of activity. And it can only blame itself and its managers for having miscalculated and misunderstood not just one, but two revolutions in the last twenty-five years: that of smartphones and that of artificial intelligence. Mistakes that are dearly paid for in a fast-paced and ruthless digital world . What in 2000 was a giant with a market capitalization of $500 billion and dominated the semiconductor industry is now reduced to a size of less than $100 billion, placing it well below fifteenth place in the global sector. Light years away from current giants like Nvidia, which understood the potential of AI before anyone else and is now worth approximately $4 trillion (four thousand billion) on the stock market. Or like the Taiwanese world leader in microchips, TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), which is around 1.5 trillion .

In 2000 it was a semiconductor giant worth $500 billion, today it is reduced to a size of less than $100 billion

Despite the support of American governments, first under Joe Biden and now under Donald Trump, who have allocated hundreds of billions to support the US-made microchip sector and have attempted to boost Intel's recovery, the Californian company has become a small fish at risk of being swallowed up by one of the giants with plenty of cash to spend . It can do little to defend itself, and to recover, it can only cut back to become even leaner. And therefore, even more exposed to the risks of a market takeover.

The path of cuts had already been taken by Pat Gelsinger, the CEO who in recent years attempted to revive Intel, but was unsuccessful. Gelsinger launched a plan to cut 15,000 jobs, bringing the total to around 100,000, but failed to recover positions either in chip production, dominated by TSMC, or in the AI device design sector, where NVIDIA and AMD excel. Intel shares lost 50% in a year, and last December the company's board decided to oust Gelsinger and put an end to his project . It took many months to find a successor, and finally, in April, the choice fell on Lip-Bu Tan, a top manager with extensive experience in the semiconductor industry. At the recent half-year results presentation, he outlined his plan: cutting another 25,000 employees, to a total of 75,000, and scrapping plans to build plants in Europe (primarily in Germany and Poland, but Italy had also been discussed). He also put the brakes on the expansion in Ohio, which both Biden and Trump had claimed as a political victory. "We are making difficult but necessary decisions," Tan said, "to streamline the organization, promote greater efficiency, and increase accountability at all levels of the company."

The arrival of Malaysian-born Lip-Bu Tan at the helm of Intel adds another piece to the multi-ethnic mosaic of CEOs at major American digital companies, right at the height of the anti-immigration and "America First" wave of Trump's Maga world. Nvidia is led by founder Jensen Huang, who Americanized his name from the original Jen-Hsun and is the son of Taiwanese immigrants, as is Lisa Su, the CEO of rival AMD. Google, Microsoft, and IBM are led by three top executives of Indian origin: Sundar Pichai, Satya Nadella, and Arvind Krishna. Uber's CEO is Iranian Dara Khosrowshahi, while South African Elon Musk leads Tesla, SpaceX, and the social media platform X.

The arrival of Malaysian Lip-Bu Tan at the helm of Intel adds a new piece to the multi-ethnic mosaic of CEOs of American big tech companies.

There was also an immigrant at the origins of Intel, but the story began with two young, all-American talents. To understand what Intel was, we must start with them, Robert “Bob” Noyce and Gordon Moore, and from the day in 1955 when they arrived in the Valley . The first was an athletic twenty-eight-year-old from Iowa whom the writer Tom Wolfe, in a biography, compared to the actor Gary Cooper. The other was a twenty-seven-year-old Californian chemist with a calm disposition and gentle manners. The person who hired them in Palo Alto, which at the time was still a valley of apricot growers, was William Shockley, a genius with an impossible character who, after inventing the transistor and waiting to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, had opened the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory to produce semiconductors. Noyce and Moore managed to last only a few years at the inventor's side, then, together with six other managers who went down in history as the "traitors", they broke away and in 1957 created a competitor, Fairchild Semiconductor.

Shockley and Fairchild, along with Hewlett Packard, which had already been operating in the area for years, are the companies that essentially "invented" Silicon Valley. However, it only began to be called that in the early 1970s, after the arrival of a new player: Integrated Electronics Corporation, or Intel for short. It was founded in 1968 by Noyce and Moore, this time leaving Fairchild to set up their own business. By then, the two had become true gurus of the Valley . Noyce had just invented the microchip, the first integrated circuit with all its components carved from a single wafer of silicon, although a series of legal disputes led to him sharing the invention with Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments. When Kilby won the Nobel Prize in 2000, Noyce was no longer with us, but he was nevertheless recognized as the other father of the microchip.

Moore, meanwhile, studied the evolution of the world of electronics, which exhibited seemingly constant characteristics. Every year, the size of devices was shrinking, while production became cheaper, while computing speed and power increased. In 1965, Moore published a landmark article in the journal “Electronics” examining this phenomenon. It argued that the number of transistors that could be packed onto a single microchip had roughly doubled every year up until then, and that the trend would continue for at least another decade. A Caltech professor dubbed this “Moore’s Law,” and since then it has become a cornerstone not only in scientific research but also in industrial production in the field of electronics. Moore’s prophecy has been supplemented over time by considerations of the performance of microchips, predicting that they would double every eighteen months, as well as by hypotheses about the constant decline in prices .

The duo of the genius Moore and the "Mayor of Silicon Valley," as Noyce was later nicknamed, were soon joined by a third Fairchild manager, the immigrant who would work alongside the two very American founders, as employee number three. His name was András Gróf, a Jew born in Budapest who had escaped first the Nazi roundups and then the Communist regime. At twenty-one, he had managed to reach the United States, taught himself English, graduated with honors from the City College of New York, and then earned a doctorate in chemical engineering from Berkeley. Meanwhile, he had Americanized his name to Andrew Grove and begun his career at Fairchild. His move to Intel marked the beginning of one of the most celebrated and significant careers in the history of computing.

Intel quickly became the dominant force in a Silicon Valley brimming with new energy , thanks in part to its own distinctive corporate culture, very different from that of Shockley and Fairchild, from which it sprang. Noyce had built the company on deeply egalitarian foundations, Moore managed its long-term vision, but it was Grove who shaped and guided it, with an approach that is well summed up in the title of his future bestseller, "Only the Paranoid Survive." Wolfe, when he described the world of Intel in his portrait of Noyce, proposed a key interpretation that has endured over time: "It's not a company. It's a congregation."

The paranoid people at Intel, among whom was another prominent immigrant, the Italian Federico Faggin, bought a two-page advertisement in the magazine Electronic News in November 1971 to announce "a new era of integrated electronics." This wasn't an exaggeration, because they were presenting the world with the first microprocessor, the 4004: a chip programmable to perform any logical function was a huge leap forward compared to single-function chips and opened the door to the imminent software boom, because suddenly the role of the technicians who could program the instructions for that system became crucial. Two young men understood this immediately when, in those years, they bought the next model of the microprocessor, the Intel 8008, in an electronics store and built a software company around it . Their names were Bill Gates and Paul Allen, and their Microsoft would soon become the major player in the digital revolution, thanks to Intel processors, giving life to the “Wintel” (Windows+Intel) alliance that dominated the world of PCs for decades.

The era of the Pentium and the "Intel Inside" stickers on every computer on Earth seemed to have marked, in the 1990s, the American company's absolute dominance in the semiconductor sector. But like many other companies in the Valley, Intel was slow in the new century to grasp the extent of the mobile phone boom, clinging to the apparent security of its computer market. However, it wasn't just the take-off of smartphones that put the giant in crisis , but a series of phenomena that have accelerated in recent years. Intel failed to keep pace with Asian rivals TSMC and Samsung in the field of advanced chip packaging, that is, new methods for manufacturing microchips, increasingly more sophisticated to accommodate digital innovation. But above all, it didn't see coming and didn't understand in time what was happening with artificial intelligence.

In the same 1990s when Intel dominated the market and was resting on the laurels of its Pentium, Taiwanese immigrant Huang and two friends opened a small factory in California called Nvidia, specializing in GPUs, the graphics cards originally designed for video games. In the years that followed, Nvidia understood that the future would be dominated by computing power and transformed itself into the producer of the core technology that all AI players need today .

Nvidia currently dominates the chip market: in 2005, Intel's CEO proposed buying it, but the idea was ridiculed. A serious mistake.

In 2005, Intel's then-CEO, Paul Otellini, sensed the impending danger and proposed to his board of directors to acquire Nvidia. At the time, $20 billion was sufficient, but the idea was ridiculed at Intel: "That's a graphics card company for video games, that's child's play. We run the world, why do we need that technology?" A misjudgment reminiscent of those made by Nokia and BlackBerry's top executives in the mobile phone industry, or Kodak in the face of the digital photography boom. Twenty years later, Intel must fight to avoid the same fate.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto