Why Poland is clinging onto coal, despite the economic and environmental costs

By Alicja Ptak

The article is part of a series by Alicja Ptak, senior editor at Notes from Poland, exploring the forces shaping Poland's economy, businesses and energy transition. Each installation is accompanied by an audio version and an in-depth conversation with a leading expert on The Warsaw Wire podcast.

You can listen to this article and the full podcast conversation on Spotify , Apple Podcast , Amazon Music and YouTube . The previous installation in the series can be found here .

In late August 2023, state-owned PGE – Poland's largest energy producer – made a surprising announcement: it planned to become carbon neutral by 2040 , a full decade earlier than it had previously declared. Even more strikingly, it said it would stop using coal – the country's dominant energy source – for electricity and heat production by 2030.

The company's plans aligned with the European Union's push toward a carbon-free future, and reflected growing investor appetite for cleaner, more sustainable assets. But in Poland, they quickly sparked a political firestorm.

The backlash came primarily from Silesia, the southern region that is the heart of Poland's coal industry. As PGE is the biggest buyer of thermal coal from Silesian mines, miners reacted to its announcement with fury.

“Who will Silesian mines sell coal to if…[PGE] intends to move away from coal by 2030?” asked Bogusław Ziętek, head of a major mining union, in an open letter to then Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. The unions demanded not only that PGE abandon its new strategy, but also that the company's CEO, Wojciech Dąbrowski, be removed.

PGE abandoned the new strategy in less than a week, but Dąbrowski kept his job for a few more months. With national elections looming in October, the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party had a bigger concern: staying in power. They failed . A new, pro-EU coalition led by Prime Minister Donald Tusk took office in December 2023 , promising to accelerate Poland's long-delayed energy transition.

But, more than 18 months later, progress has been slow . One key promise – to loosen restrictive laws on wind turbine construction – was only approved by parliament last week. The new rules, designed to unlock onshore wind development, however, may never be enacted, as the bill is expected to be vetoed by Poland's new president.

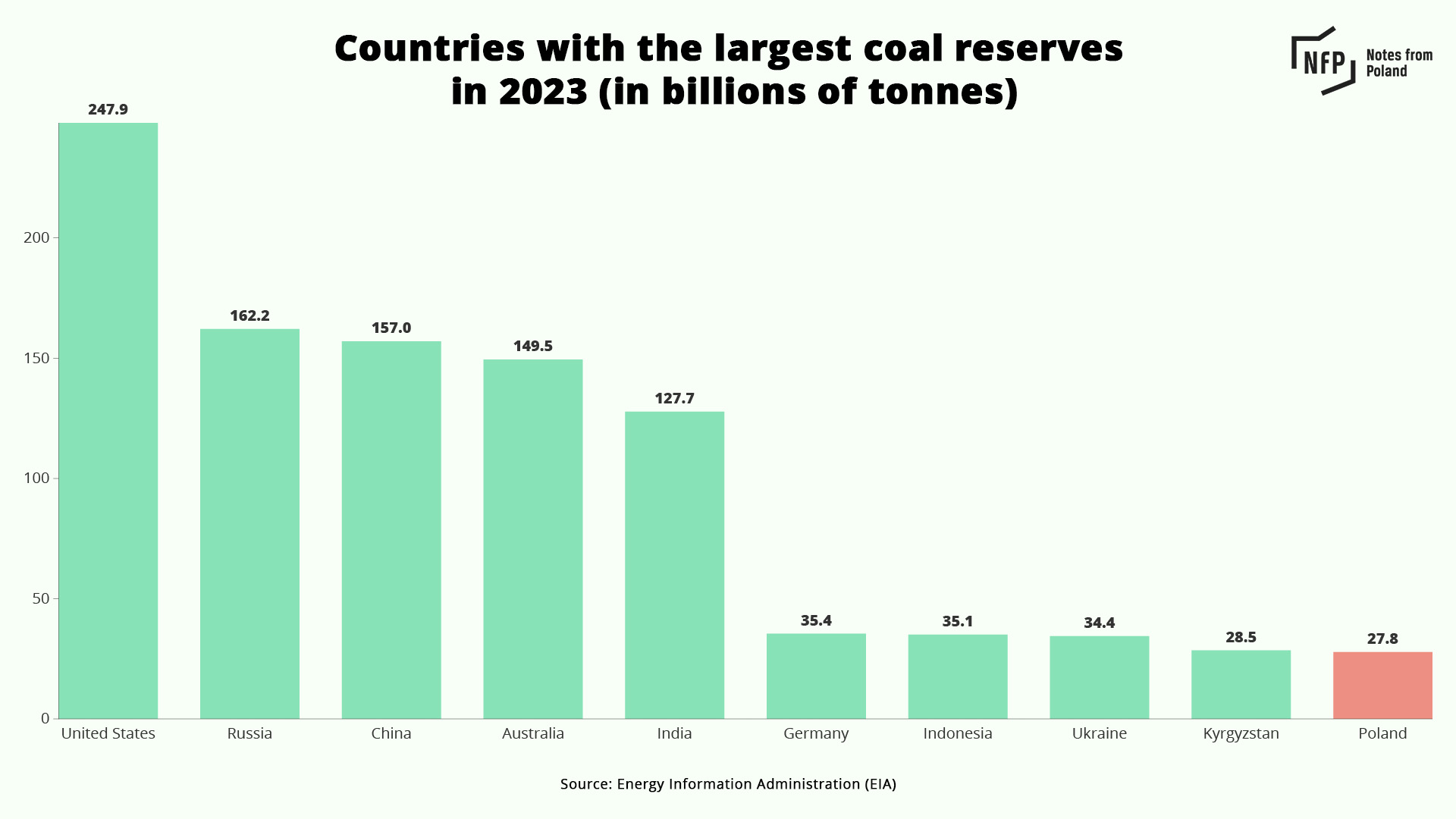

A short history of coal in PolandPoland's reliance on coal stems from a mix of its geology, history and economic legacy. The Energy Information Administration, a US state agency, estimated the country's coal reserves in 2023 at 31 billion short tons (27.8 billion tonnes), placing it second in the EU – behind only Germany – and tenth in the world.

For centuries, hard coal has been mined in Silesia, powering homes, industry and power plants. In central and western Poland, massive lignite (brown coal) operations fuel giants like the Bełchatów power station, Europe's largest emitter of CO2.

Coal's dominance in Poland was cemented during the communist era, when it became the backbone of the economy. The state prioritised coal production, not only to meet domestic needs but also to earn hard currency through exports.

In the 1970s, Poland was the second-largest coal exporter in the world. This coal-driven model persisted well into the 1990s, outlasting similar sectors in western Europe, where mines were closed due to economic inefficiency.

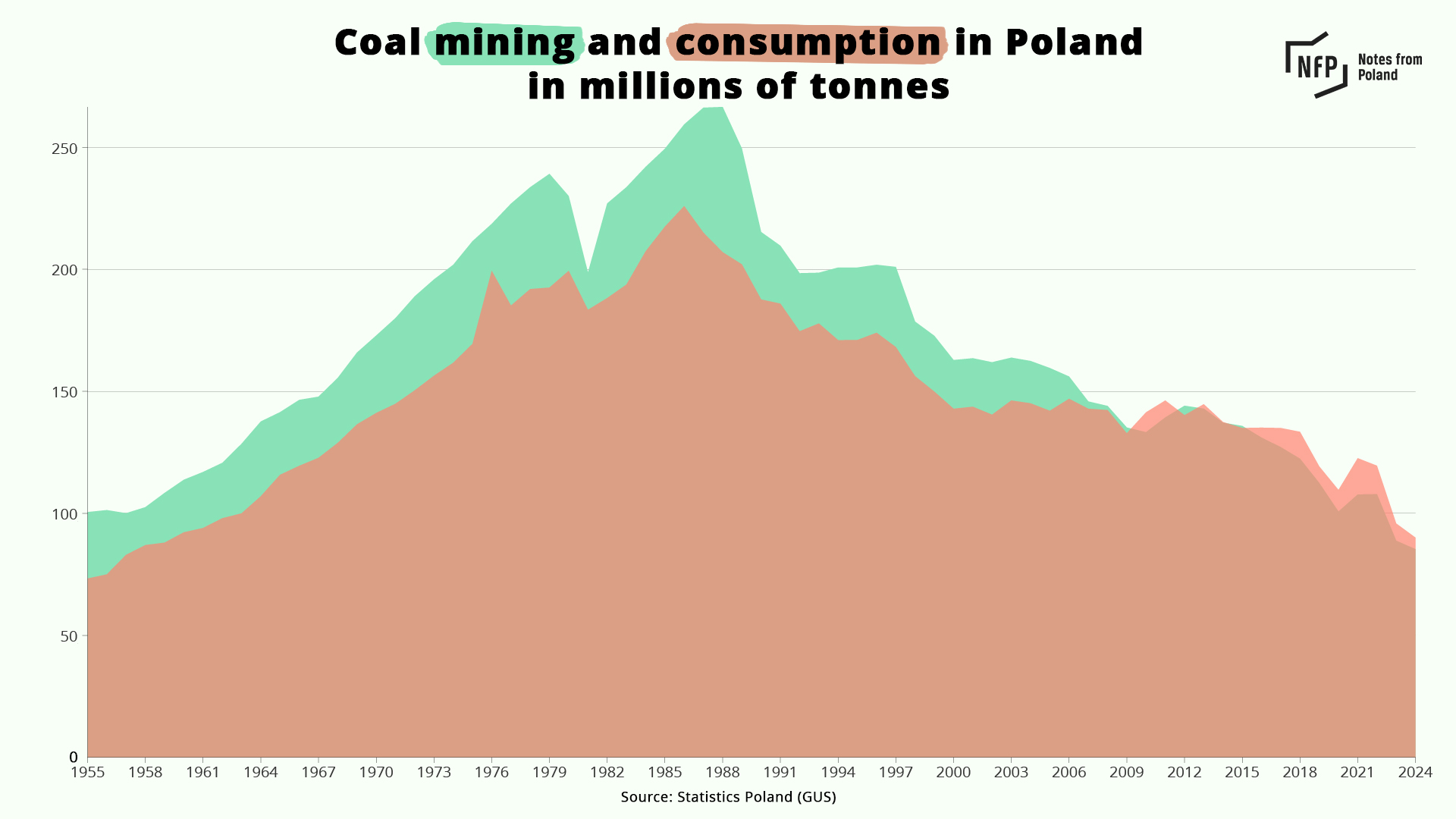

After the fall of communism and the beginning of the transition towards a free market economy, heavy industry collapsed, cutting electricity demand. Though energy use later rebounded, coal consumption never returned to communist-era levels.

Over the past four decades, annual domestic coal production has plummeted from over 250 million tonnes to about 85 million tonnes, according to state agency Statistics Poland (GUS), forcing Poland to import coal despite its ample reserves. Yet today coal still accounts for roughly 57% of Poland's electricity production, more than in any other EU country.

The decline in coal production has not been driven solely by EU climate policy. Poland's coal industry has become increasingly uncompetitive. As miners are having to dig ever deeper to retrieve it, labor costs are rising and productivity is flatlining.

That has led to the cost of mining coal in Poland being among the highest in the world, at over 900 zloty ($243) per tonne of coal produced. By contrast, the figure is 148 zlotys ($40) per tonne in the United States.

Polish coal is surviving only with heavy public subsidies. In 2025, taxpayers will spend PLN 9 billion propping up the sector. That is about 600 zloty per household, or 10% of the country's annual personal income tax revenue, calculates energy news website Wysokie Voltage.

Yet despite these economic signals, coal retains powerful symbolism, making its phase-out as much a cultural and political challenge as a technical one. It is little wonder that Poland is the only EU country without an official date to leave coal once and for all.

Why has Poland struggled to move away from coal?Poland's continued dependence on coal is not only about fulfilling energy needs: it is rooted in the country's history.

Miners have long wielded influence in Poland, especially in Silesia. Their role in resisting the communist regime – most notably during the 1981 Wujek mine protest against the imposition of martial law, where nine miners were killed – earned them lasting national respect.

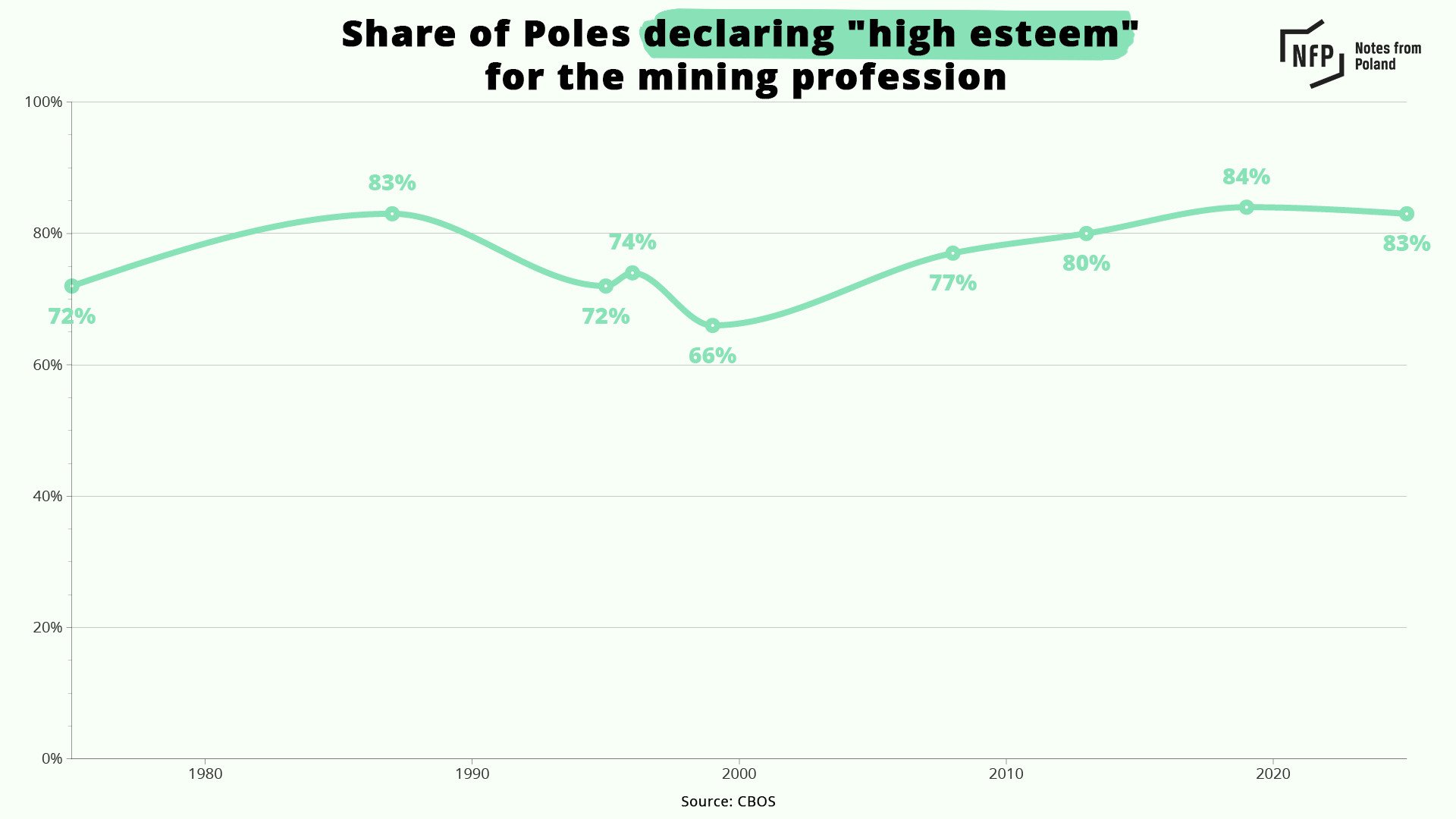

That prestige has persisted. According to state pollster CBOS, 83% of Poles said in 2025 that they have “high esteem” for the mining profession, the same share as in 1987.

In 2021, miners struck a deal with the PiS government allowing coal mining to continue until 2049, despite warnings that coal would likely be unviable long before then.

Speaking during the signing of the coal phase-out agreement, Jacek Sasin, then the state assets minister, expressed regret at the decision, suggesting it had been forced on Poland by the EU.

“The conditions and framework set by the European Union's climate policy leave us with no choice but to move in this direction and seek alternatives to hard coal,” he said, adding that mining is a vital pillar of the Polish economy and an integral part of the region's identity.

Yet that agreement will likely need to be renegotiated – on less favorable terms for the mining industry. Tobiasz Adamczewski, vice president of energy think tank Forum Energii, told The Warsaw Wire that without a new deal, “we are living in a world of fiction.”

One of the biggest barriers to cleaner energy has been political inaction. Although the rhetoric of Poland's most recent governments has differed – PiS were more openly coal-friendly, whereas the ruling coalition, at least during the election campaign, presented itself as more climate-conscious – the results have been strikingly similar.

“It's not necessarily that one government did a much better job than the other,” Adamczewski notes. “They were both quite slow to implement regulations.”

One example is the so-called 10H rule, introduced under PiS, which halted almost all new onshore wind developments. When they came to power, the current government pledged to quickly reverse it, but have delayed doing so for over 18 months – due to poor public communication and fear of a presidential veto from opposition-aligned former President Andrzej Duda.

Poland's parliament gave final approval to the wind turbine bill last week, including amendments proposed by the higher chamber, the Senate, but compared to the 2023 draft, Adamczewski says, not much has changed. “It's just a waste of time, basically,” he adds.

The bill is unlikely to become law, as the chief of staff to Poland's new President Karol Nawrocki – who came to power with PiS support – has already signaled presidential plans to veto it.

Nawrocki – who, along with many PiS politicians, calls coal Poland's “black gold” – pledged during his election campaign to ensure that Poland continues to produce “cheap energy from coal” mined domestically.

This political tug-of-war, which has repeatedly stalled Poland's shift away from coal, is nothing new.

Marcin Popkiewicz, in his book Understanding the Energy Transformation, bluntly observes that Polish politicians have been “blocking the development of alternative” energy sources for decades, regardless of their party.

Popkiewicz notes that despite “parties promising ambitious climate and environmental protection” winning a majority in the 2023 election, the government they formed later opposed key EU measures, including the Nature Restoration Law (NRL), which aims to restore degraded ecosystems across the EU by 2050.

He argues that the current ruling coalition is making a mistake by backing away from the climate commitments that, in part, helped them defeat PiS.

“[The coalition] will not get the votes of populists who support coal, timber plantations and those inflating the climate crisis, because they will vote for populist parties anyway,” Popkiewicz warns.

Additionally, years of neglecting the green transition are starting to have painful consequences for regular Poles.

Under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), companies, such as electricity producers, have paid the state for emitting CO2 into the atmosphere. Part of the proceedings – at least 50% under the law – were supposed to be used for energy transition projects.

But although tens of billions in ETS revenues flowed into the state budget – Poland has the second-highest emissions in the EU relative to its economy – they were not used to build zero-emission alternatives. Now that carbon costs are driving up household energy bills, politicians are scrambling to deflect blame.

“When I hear statements from politicians, mining unionists and energy company managers who seem shocked that the prices of [carbon] allowances translate into the cost of energy from burning coal, I feel like saying, 'You idiots, you've known this for years!'” Popkiewicz writes.

“We're in this mess of our own making, after wasting precious time and a lot of money,” he adds.

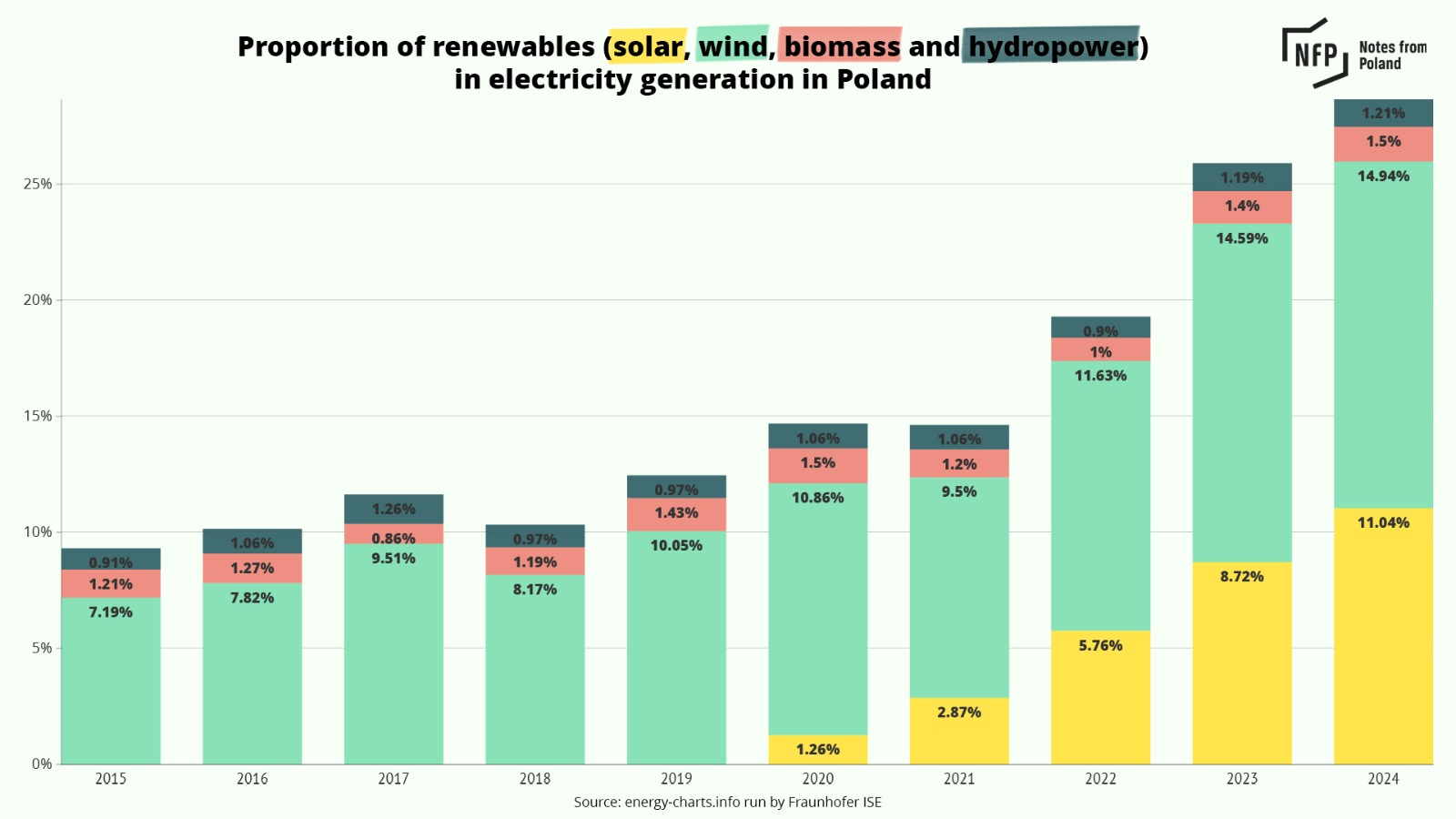

Recent years have, however, seen Poland accelerate its energy transition, especially following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since 2020, the country has almost doubled the share of renewables in the energy mix, which last year stood at 29% .

In April, Poland's monthly share of electricity generated by coal fell below 50% for the first time , marking an important milestone.

Coal is not just costly for Poland's economy, it is becoming a political trap. Over the next few years, coal will continue to dominate Poland's energy discourse, shaping electoral strategies and fueling culture wars around the EU's climate agenda.

During his election campaign, Nawrocki floated the idea of a referendum on whether to reject the EU's Green Deal, echoing demands that gained traction during widespread farmers' protests across the EU in 2024, including in Poland.

But, as Popkiewicz points out, this is legally impossible. “To do so would require rewriting dozens of directives and obtaining the agreement of most EU countries, an impossibility,” he writes, adding that the only path left for such fossil populism is Poland withdrawing from the EU.

Meanwhile, ETS2 – a new EU carbon pricing scheme covering from 2027 emissions from buildings and transport on top of the existing ETS – is already proving politically sensitive.

The new scheme is designed to level the playing field: while municipal heating and electricity are already covered under ETS, many households that burn coal or gas directly have so far escaped those costs.

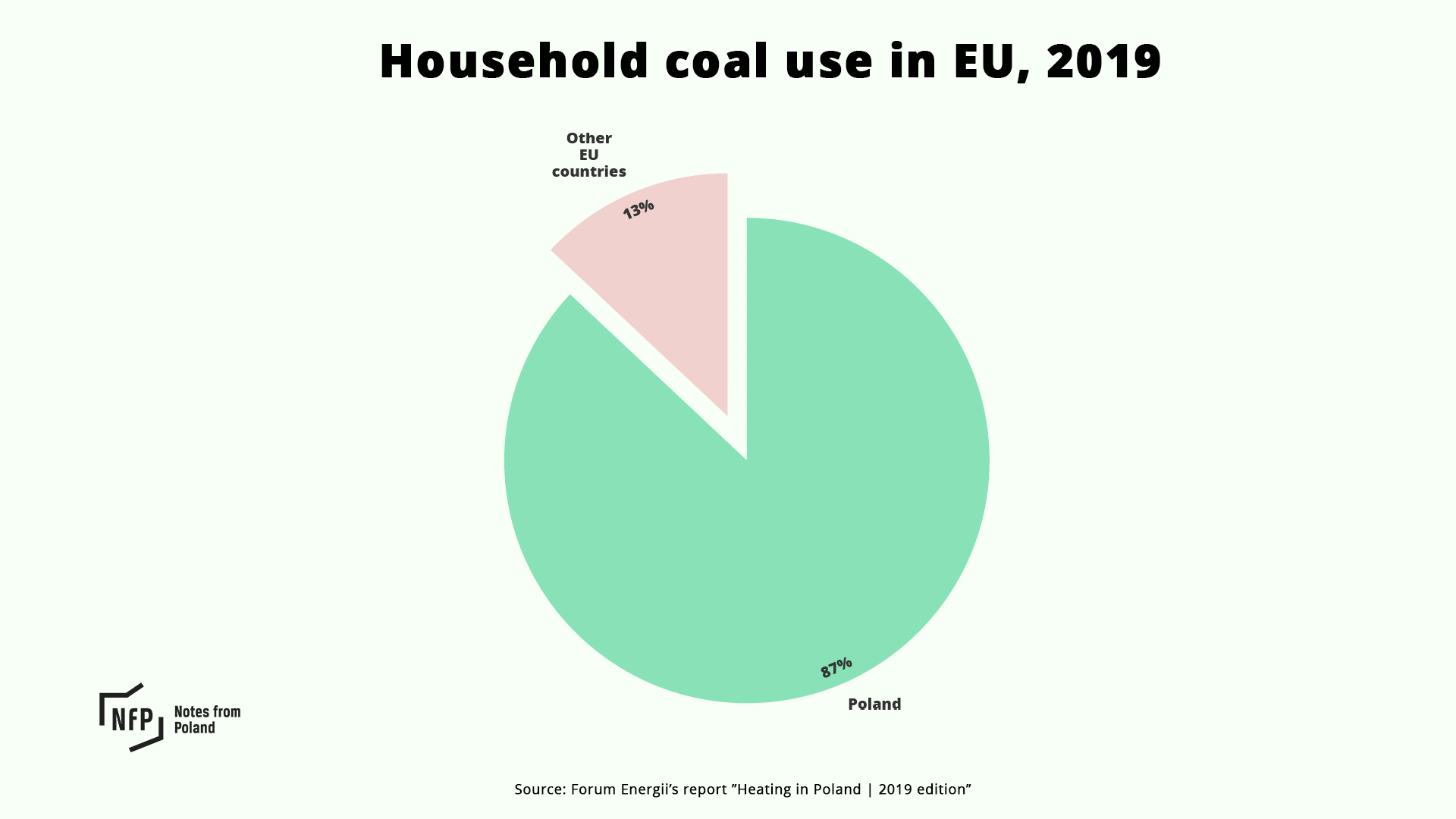

Polish households are especially vulnerable to new carbon taxes as around one third of them use coal for heating, while an estimated 87% of all coal burned in EU households in 2019 was consumed in Poland.

Adamczewski argues that ETS2 introduces fairness: “Whoever emits, pays.” But he acknowledges that the government has failed to prepare households for the changes. “We subsidized people switching from coal boilers to gas boilers,” he says. “And both of these technologies will be a problem when ETS2 comes into play.”

With new parliamentary elections due in 2027, some fear the Polish government may dilute or delay the implementation of ETS2 to avoid political backlash and to prevent handing an advantage to PiS or the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party.

And the cost is not just political. By dragging its feet on clean energy, Poland risks becoming less competitive. In 2023, companies like Google, Amazon, Mercedes and IKEA all warned that the country's coal-heavy energy mix could deter future investment .

Poland's thriving battery sector, which brings billions of zlotys in export revenues, also stands to lose out if the EU implements plans to calculate battery carbon footprints based on national energy mixes – a move that would make Polish-made batteries less competitive due to the country's coal-heavy electricity.

A coal-free future?Despite political hesitation and delays, Poland's most recent draft of its updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) marks a significant turning point. The country, for the first time, has admitted that coal will become almost obsolete by 2035. The final version of the plan is still waiting to be formally submitted to Brussels – more than a year past the EU's deadline – but the direction is clear.

Adamczewski urges the government not to weaken the plan in its final form. “The energy market and society need this investment pathway…to be implemented.”

And despite the long road ahead, he remains optimistic. When The Warsaw Wire asked if he believes in a coal-free Poland by 2035, he said that “it might even happen sooner”, noting that the economics no longer support continued reliance on coal.

“Now it's all about making sure that the local communities…are taken care of and that there is a just transition,” he concludes.

Coal produced less than half of Poland's power for the first time ever last month.

Meanwhile, the share of renewables rose to 34.2%, as Poland slowly moves away from fossil fuels.

For more, read our full report: https://t.co/WXyxQe0gQ7 pic.twitter.com/Fav6BfN8LF

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 13, 2025

Main image credit: Grzegorz Celejewski / Electoral Agency

notesfrompoland

![A large, significant road investment for the region is ready [PHOTOS]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fzycie.pl%2Fstatic%2Ffiles%2Fgallery%2F561%2F1766259_1754928410.webp&w=3840&q=100)