Mourning mother's anger at Kenyan migrant smugglers

As the sun set over Lake Turkana, a mother sobbed and threw flowers into the greenish-blue water to remember her teenage daughter who had drowned trying to reach Kenya via a new route being used by people smugglers.

Senait Mebrehtu, a Pentecostal Christian Eritrean who had sought asylum in Kenya three years ago, made the pilgrimage to north-western Kenya to see for herself where 14-year-old Hiyab had lost her life last year.

The girl had been travelling with her sister, who survived the late-night crossing over the vast lake, where winds can be powerful.

"If the smugglers told me there was such a big and dangerous lake in Kenya, I wouldn't have let my daughters come this far," Ms Senait told the BBC as she sat on the western shoreline.

Ms Senait had arrived by plane in Kenya's capital, Nairobi, on a tourist visa with her two younger children, fleeing religious persecution. But she was not to allowed to travel with her two other daughters at the time as they were older and nearer the age of conscription.

Eritrea is a highly militarised, one-party country - and often national service can go on for years and can include forced labour.

The teenagers begged to join her in Kenya, so she consulted relatives who told her they would pay smugglers to get the girls out of Eritrea.

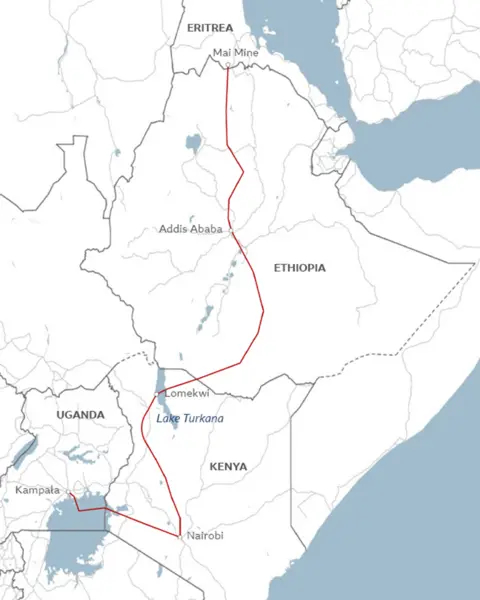

The fate of the two girls was put into the hands of traffickers who took them on a weeks-long trip by road and foot from Eritrea into neighbouring northern Ethiopia - then to the south into Kenya to the north-eastern shores of Lake Turkana, the world's largest permanent desert lake.

A female smuggler in Kenya confirmed to the BBC that Lake Turkana was increasingly being used as an illegal crossing for the migrants.

"We call it the digital route because it is very new," she said.

The trafficker, who earns around $1,500 (£1,130) for each migrant she traffics into or through Kenya (four times the average monthly salary of a Kenyan worker), spoke to us about her work at a secret location and on condition of anonymity.

For the last 15 years she has been part of a huge smuggling network that operates across Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and South Africa - mainly moving those fleeing from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.

With Kenya having stepped up patrols on its roads, smugglers are now turning to Lake Turkana to get migrants into the country.

"Agents" on the new route, she said, received the migrants in the Kenyan fishing village of Lomekwi where road transport was organised to take them to Nairobi - a journey of about 15 hours.

Warning of the dangers of travelling on the rickety wooden boats, she appealed to parents not to allow their children to make the crossing alone.

"I won't say I love the money I make - because as a mother I can't be happy when I see bad things happening to other women's children," she told the BBC.

"I'd like to advise migrants if they'll listen to me. I'd like to beg them to stay in their countries," she said, further cautioning of the callous attitudes of many traffickers.

Osman, an Eritrean migrant who did not want to give his real name for security reasons, made the crossing at the same time as Hiyab and her sister.

He recalled how Hiyab's boat capsized in front of his eyes not long after leaving the fishing village of Ileret as it was heading south-west to Lomekwi.

"Hiyab was in the boat in front of us - its motor wasn't working and it was being propelled by a strong wind," he said.

"They were about 300m [984ft] into the water when their boat overturned, resulting in the deaths of seven people."

Hiyab's sister survived by clinging to the sinking boat until another vessel - also operated by the smugglers - came to the rescue.

Ms Senait blamed the smugglers for the deaths, saying they overloaded the boat with more than 20 migrants.

"The cause of deaths was plain negligence. They put too many people in a small boat that couldn't even carry five people," she said.

During the BBC's visit to Lomewki, two fishermen said they saw the bodies of migrants - believed to be Eritreans - floating in the lake, which is around 300km (186 miles) long and 50km wide, in July 2024.

"There were about four bodies on the shores. Then, a few days later other bodies appeared," Brighton Lokaala said.

Another fisherman, Joseph Lomuria, said he saw the bodies of two men and two women - one of whom appeared to be a teenager.

In June 2024, the UN's refugee agency, UNHCR, recorded 345,000 Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers in East Africa, out of 580,000 globally.

Like Ms Senait's family, many flee to avoid military conscription in a country that has been embroiled in numerous wars in the region, and where free political and religious activity is not tolerated as the government tries to keep a tight grip on power.

Uganda-based Eritrean lawyer, Mula Berhan, told the BBC that Kenya and Uganda were increasingly becoming the preferred destination of these migrants because of conflict in Ethiopia and Sudan, which both neighbour Eritrea.

The female smuggler said in her experience some of the migrants did settle in Kenya, but others used as the country as a transit point to reach Uganda, Rwanda and South Africa, believing it easier to get refugee status there.

The smuggling network operates in all these countries, handing over migrants to different "agents" until they reach their final destination, which - in some cases - can also be Europe or North America.

Her job is to hand over those migrants who are in transit in Nairobi to agents who keep them in "holding houses" until the next leg of their trip is arranged and paid for.

By this stage each migrant has probably paid around $5,000 for the journey up to that point.

The BBC saw a room in a block of flats that was being used as a holding house. Five Eritrean men were locked inside the room, which had one mattress.

In the holding houses, migrants are expected to pay rent and also pay for their food - and the smuggler said she knew of three men and a young woman who had died of hunger as they had run out of cash.

She said the agents simply disposed of the bodies and called their deaths bad luck.

"Smugglers keep lying to the families saying their people are alive, and they keep on sending money," she acknowledged.

Women migrants, she said, were often sexually abused or forced to get married to male smugglers.

She said she herself had no intention of giving up the lucrative trade but felt others should be aware of what could be ahead of them.

It is little comfort for Ms Senait, who still mourns the death of her 14-year-old while expressing relief that her elder daughter survived and was unharmed by the smugglers.

"We have gone through what every Eritrean family is going through," she said.

"May God heal our land and deliver us from all this."

BBC