Adam Smith on Relationships between Young and Old

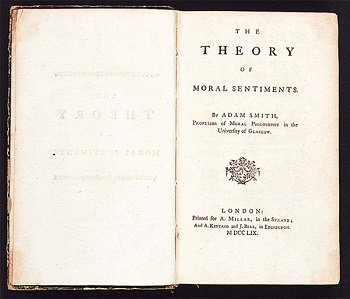

Relationships between people of different generations make up some of the most meaningful connections life has to offer. They shape deep-seated beliefs, goals, and priorities. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments [TMS], Adam Smith describes the human actor as one who is guided by relational experiences. Do relationships between the young and the old have a distinct role in moral formation?

My experience suggests that the answer is “yes.” In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith argues that one’s sense of right and wrong develops through interactions with other individuals who serve as reference points for moral approval or disapproval. In this framework, relationships are paramount, especially those that challenge our own view of self.

Sympathy is the philosophical core from which readers can draw out the massive importance of human relationships for moral formation.

- We can never survey our own sentiments and motives, we can never form any judgement concerning them; unless we remove ourselves, as it were, from our own natural station, and endeavor to view them at a certain distance from us. But we can do this in no other way than by endeavoring to view them with the eyes of other people, or as other people are likely to view them…. We endeavor to examine our own conduct as we imagine any other fair and impartial spectator would examine it.

Emotions and passions are experienced by the individual, but interacting with others and experiencing their approval or disapproval of felt sentiments results in sympathy (harmony of sentiments) or antipathy (disharmony of sentiments).

Friendship, market relationships, and family all function as “mirrors,” and these interactions can teach one to engage rightly with his or her passions. Relationships between the old and the young provide opportunities to sympathize with an altogether different point of view. Smith reflects on several benefits that emerge from intergenerational relationships, which are chronicled below.

Youthful gaiety and weathered wisdom are exchanged in interactions between the old and the young. Children relish the smallest delights, spreading laughter and joy to those around them. Smith did not have children of his own but appears to have experienced the contagion of a child’s lighthearted countenance:

- Nothing is more graceful than habitual cheerfulness, which is always founded upon a peculiar relish for all the little pleasures which common occurrences afford. We readily sympathize with it: it inspires us with the same joy, and makes every trifle turn up to us in the same agreeable aspect in which it presents itself to the person endowed with this happy disposition. Hence it is that youth, the season of gaiety, so easily engages our affections.

Sympathizing with a child’s cheerfulness changes the spectator’s view. He or she enters into the happy disposition of the child and sees challenges from a more agreeable perspective.

Though delightful, the passions of youth require temperance for practical purposes. Gaiety is not known for its protective features. Parental wisdom, gained through age and experience, is an important juxtaposition to the lighthearted folly of youth. “The first lessons which he is taught by those to whom his childhood is entrusted, tend, the greater part of them, to the same purpose. The principal object is to teach them how to keep out of harm’s way.” Though less whimsical, the instruction of parents demonstrates the virtue of prudence.

The weaknesses of youth, according to Smith, are folly and lack of self-command. One instance where Smith makes a critique of young people is in his discussion of friendship as a means of mutual good conduct and service. He writes, “The hasty, fond, and foolish intimacies of young people, founded, commonly, upon some slight similarity of character, altogether unconnected with good conduct… can by no means deserve the sacred and venerable name of friendship.” Smith’s critique may be generalized to a lack of concern for the good of the whole or service to someone other than self.

Children begin in a state of utter self-obsession, having had few opportunities to see themselves through the eyes of their spectators. “A very young child has no self-command,” writes Smith, but “alarms” its nurse or parents to tend to its discomforts. Parents can temper these outbursts, but it is not until the child enters “the great school of self-command” among his peers that he begins to see his emotions as others do. The man of “constancy and firmness” has been trained by the great school to see himself as an impartial spectator would. Though capacity for virtue is not linear with age, young people are less practiced in sympathy and self-command, and they stand to benefit from relationships with those who are well-trained.

Smith continues with a contrast between the dispositions of youth and old age. “We are charmed with the gaiety of youth, and even with the playfulness of childhood: but we soon grow weary of the flat and tasteless gravity which too frequently accompanies old age.” This comment contains a critique of those who allow themselves to be carried away by despair. The “gravity” which some fall into is not without remedy, though. Sympathy with the young reinvigorates a weary heart:

- That propensity to joy which seems even to animate the bloom, and to sparkle from the eyes of youth and beauty… exalts, even the aged, to a more joyous mood than ordinary. They forget, for a time, their infirmities, and abandon themselves to those agreeable ideas and emotions to which they have long been strangers, but which, when the presence of so much happiness recalls them to their breast, take their place there, like an old acquaintance, from whom they are sorry to have ever been parted, and whom they embrace more heartily upon account of this long separation.

Happiness is a passion that flows naturally from youth but must be cultivated in old age, especially when one is plagued with infirmities. Entering into another’s experience through sympathy can offer a refreshing alternative to the habits of the mind.

Gaiety and joy are perhaps more visible than the virtues of the elderly, but those in old age are far from lacking in moral abilities. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith reflects upon humanity’s preoccupation with ease, utility, and distinction through the parable of the poor man’s son. During his youth, the poor man’s son wants to attain the conveniences of the rich. He believes that a palace, a carriage, and personal servants will provide him contentment and proceeds to work tirelessly to attain these luxuries. In the heat of ambition, the poor man’s son “sacrifices a real tranquility that is at all times in his power” and abandons “humble security and contentment.” In old age, the poor man’s son discovers that “wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility,” providing no more peace of mind than a tweezer-case.

Smith admits that most men fall for the same empty promises as the poor man’s son. They imagine that all the trinkets of the rich man are the means to greater happiness. Foolish ambition—a dangerous vice—loses its appeal with the man of old age.

- But in the languor of disease and the weariness of old age, the pleasures of the vain and empty distinctions of greatness disappear. To one, in this situation, they are no longer capable of recommending those toilsome pursuits in which they had formerly engaged him. In his heart he curses ambition, and vainly regrets the ease and the indolence of youth, pleasures which are fled for ever, and which he has foolishly sacrificed for what, when he has got it, can afford him no real satisfaction.

Experiencing weakness through age and disease results in wisdom that the young, ambitious man lacks. Smith does not condemn all ambition—it motivates people to cultivate, build, and invent. Despite its benefits, Smith maintains the view that ambition is a “deception” of which young people must be warned. The elderly person who has tasted what life has to offer guides the ambitious young man who is mistaken about the source of happiness. The narrative of the poor man’s son offers Smith’s readers the chance to sympathize with the character’s disappointment and proceed soberly.

Beyond highlighting the differences between the old and the young, Smith makes a strong claim regarding the dignity of the old. He says that one’s treatment of the elderly indicates virtue: “The weakness of childhood interests the affections of the most brutal and hard-hearted. It is only to the virtuous and humane, that the infirmities of old age are not the objects of contempt and aversion.” It is easy to respond kindly to a child, but the virtuous response may not be natural. Sympathy transforms our natural inclinations and aversions, making it possible to move past a transactional approach to relationships.

I believe Smith would encourage individuals to cultivate relationships across generations as part of their moral development. The benefits of such relationships illustrate Smith’s view that moral faculties are developed in social settings through the exchange of sympathy. Each season of life comes with sentiments that complement the emotions and passions of others, giving each child, parent, grandparent, and mentor a part to play in cultivating virtue.

[1] The Theory of Moral Sentiments, by Adam Smith. 110.2

[2] TMS 110.3

[3] TMS 42.3

[4] TMS 212.1

[5] “The care of the health, of the fortune, of the rank and reputation of the individual, the objects upon which his comfort and happiness in this life are supposed principally to depend, is considered as the proper business of that virtue which is commonly called Prudence” (213.5).

[6] TMS 225.18

[7] TMS 145.22

[8] TMS 145.22

[9] TMS 146.25

[10] TMS 246.21

[11] TMS 42.3

[12] TMS 181.8

[13] TMS 181.8

[14] TMS 182.8

[15] TMS 183.10

[16] TMS 219.3

Anna Claire Flowers is a Ph.D. student in Economics at George Mason University. She earned a BA in Public Administration and a BA in Economics from Samford University. Her research interests include family economics, in particular the economic significance of family relationships and the economic factors that influence family decision-making.

As an Amazon Associate, Econlib earns from qualifying purchases.econlib