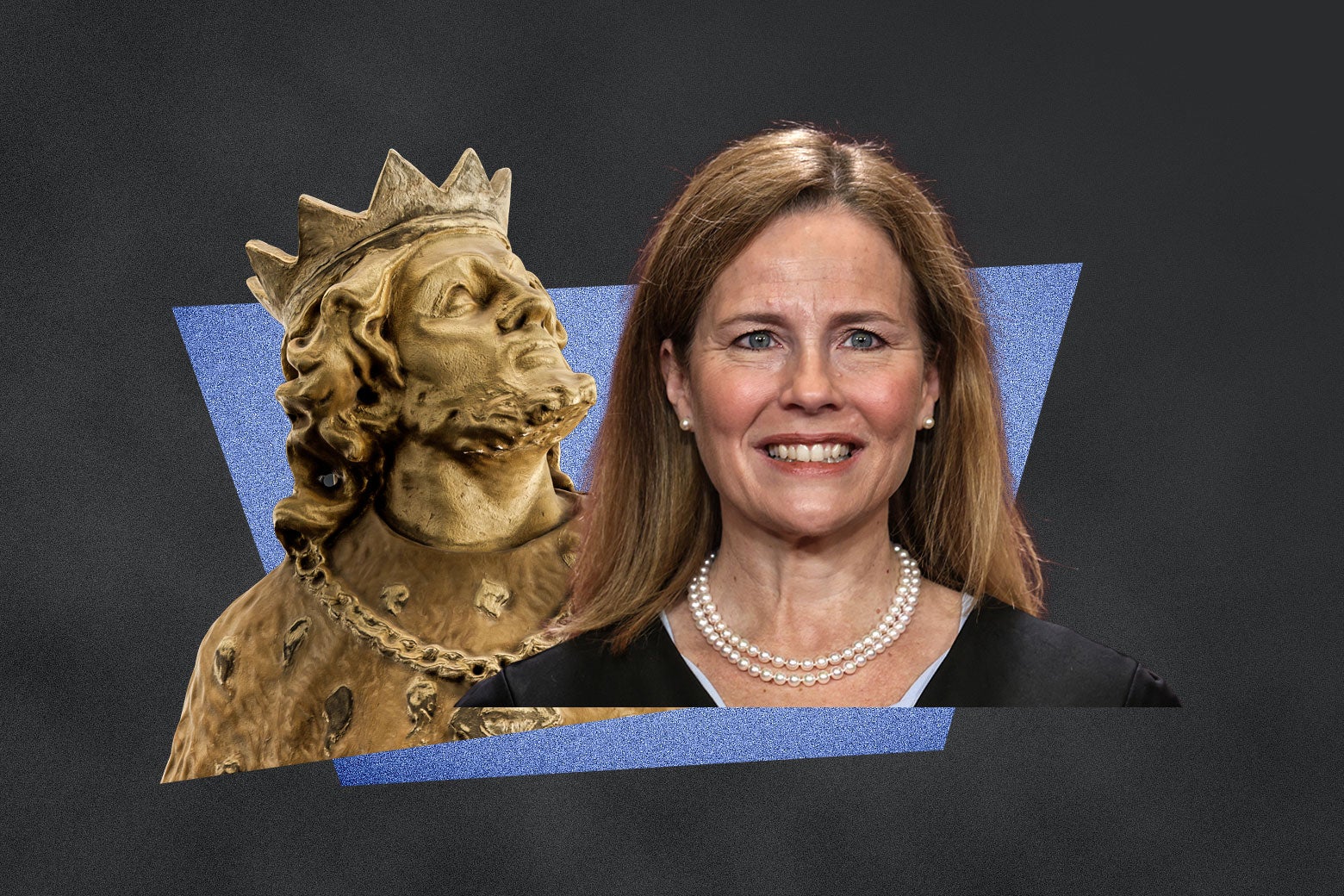

Amy Coney Barrett Somehow Managed to Get the Law and the Bible Wrong in Her New Book

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett's new book, Listening to the Law , excerpted in the Free Press on Wednesday, features a discussion of King Solomon. Barrett believes that the biblical king's ruling about two mothers fighting for custody of a child can explain the difference between “doing justice” and applying the law, with the latter being the proper role of an American judge, according to Barrett. Remarkably, the justice manages to get both the Bible and the legal system wrong.

The judgment of Solomon, found in Chapter 3 of 1 Kings , is one of the most familiar stories in the Hebrew Scripture. As Barrett describes it, Solomon “famously mediated the dispute between two women claiming the same baby” by proposing “to divide the baby in half, betting that the true mother would relinquish the child rather than see him die.”

To Barrett, “Solomon's wisdom came from within,” rather than from “sources like laws passed by a legislature or precedents set by other judges.” His authority was “bounded by nothing more than his own judgment.” In contrast, Barrett says, American judges, including Supreme Court justices, must apply the rules found “in the Constitution and legislation,” without consideration of their personal values, no matter how Solomonic they may seem.

That is a serious misinterpretation of the story. Solomon was neither making a moral judgment nor applying his own understanding of right and wrong. Instead, he was reaching a purely factual determination while carefully adhering to the background law.

The pure legal principle in the dispute, from which Solomon never strayed, was that the true mother must be awarded custody of the child. We might call that biblical common law, a rule beyond question. Thus, Solomon never considered the best interest of the child or the women's respective nurturing abilities. He did not base his ruling on “innate wisdom or divine inspiration.” Factual parentage was all that mattered under the law.

Solomon's sole objective was to decide which woman was the actual mother and which was the mother of another boy, one who had passed away—his goal was not to invoke his personal concept of justice. As he recounted, “One says, 'This is my son, the live one, and the dead one is yours'; and the other says, 'No, the dead boy is yours, mine is the live one.' ”

Solomon then figured out how to expose the liar. His threat to divide the baby was a credibility test, the equivalent of high-stakes cross-examination. It may well have been a bluff. The true mother's immediate outcry was demeanor evidence, which allowed Solomon to render an accurate verdict, conforming to the underlying law.

“If a judge functions like Solomon,” writes Barrett, “everything turns on the set of beliefs that she brings to the bench.” This is descriptively incorrect. Solomon's beliefs played no part in his judgment, other than his conviction that he was called upon to award custody to the child's own mother.

It is disappointing, though not surprising, that Barrett fails to recognize Solomon's role as the sorter of fact. Apart from three years as an associate at a law firm, she has spent her entire career in academia or appellate courts. It is entirely possible that she has never examined a witness at trial.

Accurate fact finding, however, is the essential first step in any judicial system, a process the justice mentions not at all. Justices Sonia Sotomayor, a former prosecutor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson, a former public defender, would not have made the same mistake. Their years of experience in the trial courts surely taught them that there is more to justice than a review of the appellate record. Barrett extols a judge's obligation to “resolve disputes according to the ground rules that the people have prescribed,” but that responsibility is meaningless in the absence of reliable evidence.

The Bible itself recognizes that the essence of Solomon's wisdom was his ability to find the truth. The night before he heard from the two women, the king prayed for “an understanding mind” to judge the people, and the Lord in response granted him “discernment in dispensing justice.”

It was indeed those qualities—understanding and discernment—that Solomon engaged in the women's case. Contrary to Barrett's account, his ruling was bounded by both law and fact, not merely by “his own judgment.”

Barrett offers a misreading of King Solomon as a strategic foil for her idealized American judge, who obviously never needs to worry about facts. Like her mentor, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, Barrett claims to be a strict textualist. It is therefore unsettling that even the Bible is not sacrosanct when she wants to make a point.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.