Elementary, Watson! Glory and damnation of the mad scientist.

The elephant's editorial

The sublime paradox of the discoverer of DNA, who died almost a hundred years ago, who after having explained to us well who we are and how we are processed in our vital molecule, began to rant about blacks, women, fat people.

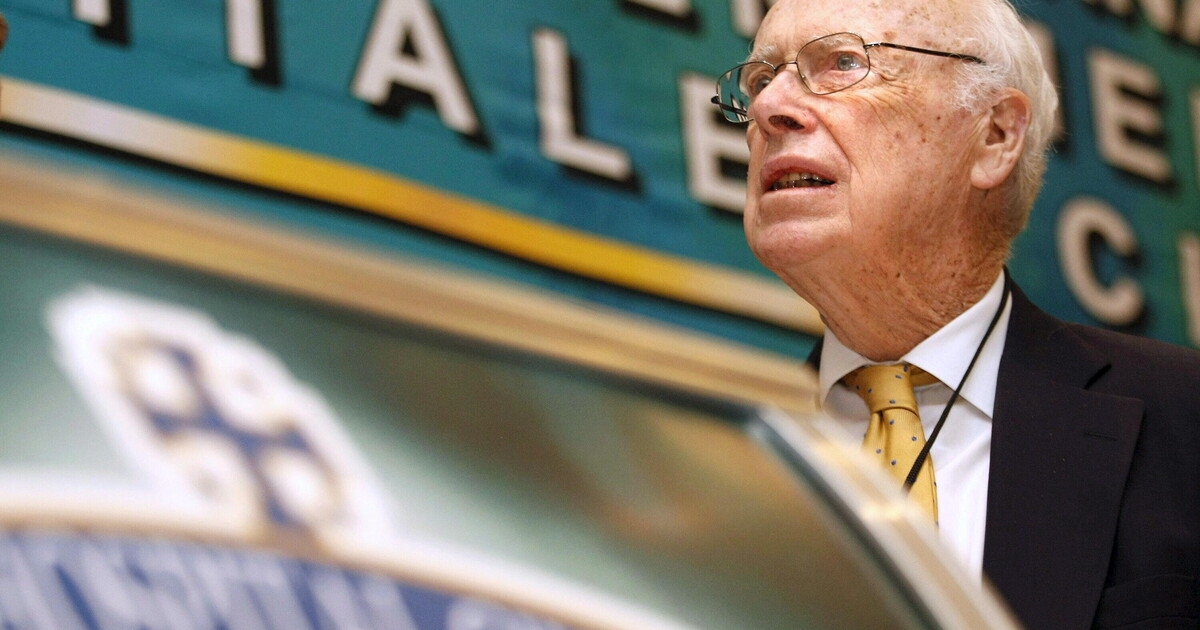

The great thing about James Watson , whom I intercepted at the Met many years ago while he was toasting with his DNA counterpart, Francis Crick, two warbling gentlemen during the interval, is that he was crazy. After explaining to us in detail who we are and how we are processed in our vital molecule, the spiral or double helix, he began to rant about blacks being less intelligent than whites, about women, and I'm not even mentioning fat people , a personal insult I can't forgive him for: I would never hire a fat guy, a fat person, he said. The writer and mathematician Chiara Valerio , who knows things, I believe, but can't explain them, I'm sure, dedicated a super crocodile to him in which she compares him to Pythagoras and Copernicus; the usual Einstein wasn't enough, and even Schrödinger or Heisenberg were all nonsense. But he forgot to say that he was crazy, a wise madman , cognitively very sound, incorrect to the point of getting himself expelled from all the institutions that count, despite the 1962 Nobel Prize , despite the fatal article of nine years earlier, despite the publication of his personal DNA.

Having died at 97, lucky him, he doubted everything, including himself. He wasn't a depressive type; on the contrary, he was full of humor and happy with his incredible scientific and social success, which he talked about so he could have it all to himself, according to his detractors, especially excluding Rosalind Franklin , a woman, or rather a biologist, who had been a companion in discovery but was not recognized by Stockholm's academy of illustrious beards. The mad scientist is a myth that, thanks also to Watson, has endured throughout the last century, with a long-standing legacy in this one. We always enjoy connecting special relativity with Einstein's sticking out his tongue, his grimace at the universe. We don't know very much, due to incompetence, about space and especially about time, which Augustine said he could only know if he didn't think about it, which Plato resolved into a moving image of eternity, which Aristotle, more modestly, described as the number of movement according to before and after. But we know quite a bit about these somewhat absurd lives, far removed from the scandalous Victorianism of a Darwin, from the mental and physical clichés of a Fermi or a Marconi, ordinary people with exceptional destinies, including those who explained the so-called biological mystery of life to us by starting from a very, very eccentric way of living their lives. Who knows what connects certain unique discoveries, the sophisticated elaboration of knowledge, to the original spirit of the professor in the clouds, to his countercultural experience, to his not being an intellectual of his times.

Valerio in La Repubblica doesn't even devote a single line to Watson's patently insane anti-woke counterculture, while the stern and censorious New York Times dwells with hyper-correct punctiliousness on all the misconceptions of the scientist who had the right idea and was able to convey it to the world, to biology, to medicine. They called him the Caligula of biology ; he wrote "The Double Helix," an autobiographical essay compared to the Federalist Papers as one of the hundred most important works of American literature. I believe that having taken us very seriously, decoding the structure of being with a precision superior, let's say, to that of existentialist philosophers and other humanists, Watson then wanted to mock us with devilish cunning, also to test how free we were to listen to those who know things when they say things they don't know, a sublime paradox of a superscientist who died almost a century old between glory and damnation.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto